- Home

- David Loftus

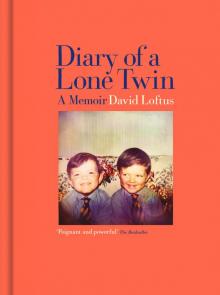

Diary of a Lone Twin

Diary of a Lone Twin Read online

To my three graces, Ange, Mother and Pascale, and their d’Artagnan, Paros.

Contents

WINTER/SPRING

IT FEELS A LOT LIKE SUMMER

AUTUMN

CODA

Acknowledgements

WINTER/SPRING

‘You can’t get to the meadow of happiness without climbing the cliff of hardship.’

OLD TIBETAN PROVERB

Monday 1 January

Riad El Fenn, Marrakech

New Year’s Day, and thus begins my personal diary of the year, an odyssey in which I will try to come to some sort of understanding of the events, thirty years ago, that so shaped my life: the death of my identical twin Johnny. It shouldn’t read as vengeful or vitriolic, but I want to tell the truth in as few pages as possible, over 300 days, from New Year’s Eve to the anniversary of John’s death. I will try to be as honest and open and transparent as I can, leaving myself psychologically and emotionally bare, telling the story as faithfully as I can and showing the ultimately positive and cheerful me that lives and breathes today. There’s no point in this painful journey unless the truth, and the telling of it, helps others who have lost loved ones, not just identical twins, but brothers, sisters, partners, friends and children.

Today I’m in a rather sad and contemplative state. I can’t be sure as to whether I will complete the first day of this journey, let alone the whole year. Where to start? Sitting here in the shadow of the Koutoubia Mosque in ancient Marrakech, a place I have come to call my ‘home from home’, seems as good a place as any. As does the first day of the year. I have just watched the sun set over the palms beside the mosque’s melodic call to prayer, disturbing the sparrows as they rush to their nightly evensong conventions in the trees and vines of the riads. Half an hour of incessant chatter and then blissful silence. I watch and listen nightly.

How to start? Last year was the thirtieth year since John died. Thirty years of surviving as a singleton after spending nearly half my life as an identical twin. And what do I hope to achieve by dedicating myself to this year of exploring the loss? Will this be a cathartic experience, a voyage of self-discovery, or will it end in sadness? Time will tell. The desire to write something has been with me for many years, fuelled by a deep sense of injustice surrounding the nature of Johnny’s death, alongside a festering guilt around the events that led to it. Plus a feeling that this has to be confronted and faced.

Since John died one of the simplest of everyday tasks has become one of the most heartbreaking for me: the act of shaving. I had shaved John while he was in hospital and the contours and blemishes of his face were so familiar to me, akin to looking in the mirror. After that, the task of shaving myself became an impossible chore. That feeling has never left me, and the feeling I have on day one of this journal is of facing a very large, very clear mirror, for the first time since his death.

Tuesday 2 January

I’m here in Marrakech to see in the New Year with Ange. My day has been spent sunbathing. No longer deemed fashionable or indeed safe, tanning to both John and I was deemed quiet, solo, ‘me time’. A time to liberate ourselves from the use of our primary sense, sight. I was thinking today of the combined hours, indeed weeks and months, we spent in that semi-catatonic state of rest, listening to the sound of the sea and the wind in the olive and casuarina trees on the Greek island of Paros, drinking in the smell of drying oregano and thyme in the intense Aegean heat. To many it might seem wasted time, but some of our best ideas came from these sun-baked, silent moments. Today as I listened to the mosque’s call to prayers, smelt the cinnamon and spices in the air and watched the high-flying storks sailing in the winds from the Atlas Mountains, I started thinking about John’s early joy of writing poetry. Aged eight or nine we were both often to be found at my father’s desk or at the dining table drawing and painting, but occasionally he would wander off and hide to write a poem, usually addressed to our parents. I found one recently:

Beautiful Things by John Loftus

Beautiful things that look a sight

Make the world nice and bright

The red is the sun, the white the moon

The black is the night, the pink is the noon

Colourful butterflies in the air

On a plate, a golden pear

Little red berries on a hawthorn tree

And an elegant bumble bee,

The nice little ducks are on a flight

And a child’s flying kite

The coloured shirts of a football team

Freshly pulled vegetables, mostly green

Blue is the sea, the river too

On the grass, a silver dew

The daisies and buttercups are very small

The people like them one and all

Don’t forget the purple heather,

And the grass that is as light as a feather

The owl is known to be very wise

Bird watchers watch him with beady eyes

All things are beautiful

Not like a beastly bull

All these things, God made them all

All these things, great and small

Finding this was a glorious reminder of the innocence and simplicity of our youth. John and I would kneel and say our prayers nightly, either side of the bed. We’d pray for our parents and maybe our little sister and brother if they hadn’t annoyed us too much. We’d pray for an end to wars, we’d pray that there wouldn’t be another Ice Age, and we’d both pray that we’d never, ever get a brain tumour.

Wednesday 3 and Thursday 4 January

Last night at Riad El Fenn, Marrakech

Flying home from Marrakech with Ange, I’m thinking about brain tumours . . . what made our young minds fear them so? The Ice Age fear stemmed from a very early dream I’d had, when creeping down from the North Pole came a wall of ice hundreds of feet high, crushing everything in its path. But brain tumours? I can’t remember why. Mother, being a doctor, would occasionally talk over tea with my father about her day’s events, but we were normally ignorant of the medical phrases we’d hear, like spina bifida and toxic shock syndrome.

Our first encounter with brain cancer was on our first ‘solo’ trip abroad as twins. Unaccompanied by our parents, at fourteen or fifteen years old we were sent to stay in Ontario during the summer of 1976, the UK’s great drought. We stayed with our Uncle Almond, best known for being the country’s leading nuclear scientist, but more interesting to us boys as the inventor of the ‘bluey whiteness’ chemical in Daz’s washing powder. Alison and Lesley, his twin daughters, were fascinating to us, and us to them – our first experience of non-identical twins. They were fiercely different and often fought like cats and dogs, but John had a crush on Cousin Alison and I had a soft spot for Cousin Lesley.

They introduced us one night to a boy called Billy. He must have been about eighteen or nineteen and we were both drawn to his recklessness. He owned a silver Ford Pinto, a car more akin to an episode of Thunderbirds than the boxy, sensible cars of home. He’d souped-up the engine and on the first Sunday of every month he took it to the local diner to hang out, and occasionally to drag race up a mile of open road. One time John and I lay side by side, holding hands in its weird space-age boot as he took part in one of those illegal contests. We were both terrified but didn’t admit it to each other for days. Billy was bonkers, wildly irresponsible and – to us – as cool as a cucumber. It was only later, during a long and uncomfortable lecture from Uncle Almond, that we learned his abandon stemmed from the removal of a very serious tumour from his brain and the insertion of a metal plate in the part of the brain believed to govern sense or reason.

Flying into Montreal that summer, our first landing in a plane other th

an a few turboprop European jaunts, was scary. Our descent took place during an extraordinary flash storm, with lightning hitting the plane twice, but it was accompanied on our starboard side by the most beautiful double rainbow.

It was the first of three times in my life that I have flown through a rainbow, the other two when I was flying co-pilot. As one nears the rainbow, it seems to shrink, with the arc getting tighter and tighter, until, for a few moments, it forms a perfect ‘halo’ around the aircraft, moving at the same speed, bathing the cockpit in an extraordinary kaleidoscopic glow. If one had to visualize the ideal ‘gates to heaven’, this must surely be it.

Saturday 6 to Tuesday 9 January

The Mews

‘A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies.

The man who never reads lives only one.’

—GEORGE R. R. MARTIN, A DANCE WITH DRAGONS, 2011

Lying here at home in the Mews, contemplating a rather uneventful photoshoot today, I gaze at my bedside wall covered in a collage of front covers and pages from the magazine The Graphic from the 1870s. Scenes range from a newly discovered parakeet from an exotic land to a map of Paris, surrounded by the Prussian artillery. Browned or bleached by the sun, worn by over a century’s page turnings, the pages are collaged together to create a wallpaper of antiquated typography and engravings.

One of them depicts my hero Alexandre Dumas. Somehow I had always imagined Dumas as the handsome and courageous hero Edmond Dantès in The Count of Monte Cristo, but handsome devil he is not. Portly, moustachioed and sporting what can only be described as a wild afro, he stares down at me now, challenging me to write, to keep going onward, regardless.

For many years The Three Musketeers was the benchmark novel I compared all other books to, until I read The Count of Monte Cristo, which remains my desert island book. When I told John I had finished it, he told me he had already read it, but refused to be tested on it. I didn’t believe him for a minute. Competitive reading lasted all our lives. In the early years it was who could read Janet and John without being corrected. Later it was who could read Emil and the Detectives faster or Asterix the Gaul in French. I once gave him a copy of Tintin’s The Black Island in Greek and fibbed that I had translated it into English. Later in life the competitiveness grew, but it was more, ‘my author is better than yours’. Where he read Mervyn Peake, I read Michael Moorcock. Where he read Tolkien, I read Camus and Kafka.

Now I can’t remember a single character’s name from Michael Moorcock. John the Elder was right there. For fifteen years I refused to read The Lord of the Rings. Why would I read what was considered a children’s book when I could be reading Jack Kerouac? Orcs? Or cool chicks in berets smoking unfiltered Gauloises, listening to abstract jazz and driving in old convertible Cadillacs across the States?

Four years after John’s death I took his copies of The Lord of the Rings to Paros, the Cycladean island John and I had shared as a summer holiday destination for many a year. He had two copies, almost identical, paperback and tatty. One had been read by him four times, and the other three. He’d read The Lord of the Rings seven times! Not only that, but he had read it each time without reading anything else, so back to back. Like painting the Forth Bridge; finish the book, and start again.

For three and a half weeks I caught the little caique fishing boat across the bay from Parikia port to Livadia. I would wander the sun-baked pathway, passing the solitary nudist on his rock (we nicknamed him ‘Adonis the Bronze’), to our little beach at Agios Fokas. It was always deserted, because it was stony rather than sandy, and facing out into the deep Aegean blue, I would sit under the casuarina trees and read about hobbits, orcs, fairies and dwarfs.

Jane Apostopolous was our landlady in Paros for many years. At the end of John’s last stay he trudged up the mountain to the Yria potteries in Lefkes and bought Jane a little blue pottery bird, a love bird. It was part of a pair; there was a light and a dark blue one, but he could only afford one. Jane adored it, popping it on one side of her mantelpiece. Two weeks later, I also came to stay at Jane’s with my oldest chum, Peter Hornsey. We roasted ourselves at Agios Fokas, him reading Stephen King, me with my Beat novels, sharing cassettes of The Cure and Nick Cave. At the end of our three and a half weeks I also trudged up the mountain to Yria in Lefkes and purchased a small dark blue bird that had been part of a pair. When I presented it to Jane she burst into tears and placed it next to its other half. I hadn’t known that John had bought the lighter one. Sadly, John would never return to Paros.

I left one of the copies of The Lord of the Rings on her mantelpiece, next to the two birds, and haven’t been back to Paros since.

Tuesday 9 January

The Mews

Having passed my first week of writing without slipping into a pit of depression, I have begun to assess how much I can mentally cope with in this Year of Living Retrospectively. A to-do list, I think, must begin with a return to Paros. When my son was born I wanted to give him a name that somehow honoured the memory of my dear twin, but to call him Johnny seemed too much, so we called him Paros, after the island of our shared adventures. Paros Erik (after my father) Loftus was born 21 June at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

Wednesday 10 January

Apparently the bluebirds over the white cliffs of Dover were actually swallows and house martins, which, upon close inspection, have a blueish sheen to their black plumage. I saw my first true bluebird in summer last year, in the Catskills of upstate New York, an identical pair of vibrantly iridescent males.

I’ve been drawn to birds since I was nine or ten. I didn’t know until recently that, as the younger twin by an all-important ten minutes, I was often following in John’s footsteps in many of my hobbies. By that age he was already showing signs of being a much more talented artist than me. And while I was struggling with my piano scales, John was a natural on the ivories, soon Scott Joplin-ing away on our mother’s Steinway. Unbeknownst to me, my parents were quietly discussing their worries that I didn’t have quite as many hobbies as John. He was not only winning Blue Peter gold badges for artistic endeavours, but also researching and hand-painting entire battalions of Napoleonic soldiers, creating exhibitable LEGO structures and transporting all these and more in his perfectly maintained Hornby train set. Maybe, in hindsight, he was trying to cram more into his life.

I was drawing and reading like a demon, but I struggled to be passably good in so many of the things he excelled at. Only now do I see that my father’s wanderings through Richmond Park with a pair of binoculars, trailing a cold and puzzled me, were a (successful) attempt to interest me in ornithology. Later, too, the gifts, firstly of a little Kodak box camera, and then an Olympus Trip, along with second-hand copies of Camera magazines, were his successful attempt to interest me in photography. One (photography) is now my chosen career, the other (ornithology) one of my greatest pleasures. To sit in a garden, field or wood, to close one’s eyes and just quietly listen to the sound of birds is music for the heart and soul.

Thursday 11 January

The Mews

Fraternal, or non-identical, twins come from different eggs within the mother’s womb. The eggs happen, by chance, to be fertilized by different sperm from the father at around about the same time. Both eggs – or ova – then begin to divide and develop at about the same rate. They can be the same sex or they can be brother and sister and they will look as similar as any other brother and sister – they just happen to share the same womb for nine months.

Identical twins are a different kettle of fish. A single ovum is fertilized by a single spermatozoon. This, by a freak of nature, doubles and then separates into two separate embryos sharing parts of the same foetal membrane. These identical embryos grow entwined and bonded by this extraordinary and still hardly understood oddity in human development.

* * *

When I first altered my career course from illustrator to photographer, Traveller magazine sent me on a commission to photograph an article celebrating

Greek Orthodox Easter in Cephalonia. It was a beautiful piece by Louis de Bernières describing the slaughtering of goats, midnight processions of priests and ancient icons, feasts and firework fights in the streets. It must have been four or five years since John had died and I flew to Cephalonia and jumped in my Durell-esque taxi to the small fishing port of Fiskardo. From there it was a short boat ride to Ithaca, Homer’s home for Odysseus. An hour’s walk along the deserted seafront of Vathy and I arrived at my little pension. It was stunning, a deep Tuscan yellow, clad in bougainvillea, with deep green wrought-iron chairs looking out over the blue Ionian Sea.

When John was twenty years old he travelled out to Paros alone, his first time away by himself, accompanied only by his Tolkien and an old scouting tent. Worried sick that he hadn’t called to catch up on cricket scores (a twice-a-week habit) or written a beautifully illustrated postcard (a once-a-week habit), I travelled to Paros to find him. Twenty-four hours later I discovered him reading in his tent near Agios Kokus, malnourished, dehydrated, suffering migraines and tearful. After tea and cuddles and a good souvlaki or two he quietly buried his head in his hands and made me solemnly promise to ‘never go travelling on my own’.

Now here I was, on my own, unlocking the door to my room all these years later. I threw my camera bag and notebooks all over the bed and sat quietly for a few moments. I moved to the wicker chair in the corner, then I moved to the stool by the window. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know where to sit, and I didn’t know how to act. I remembered my promise to John and it dawned on me I was about to spend my first night alone, not only since John had died, but since we had been conceived.

John and I loved each other immensely, immeasurably, but I probably only appreciated how immense this love was once he was gone. In the unreal, unbelievable silence that followed his dying, dawned the unimaginable truth that he, who was the wiser, the more talented one, and my leader by ten important minutes, was gone. I was in the state most people are in, for the first time since conception and cellular division: a singleton.

Diary of a Lone Twin

Diary of a Lone Twin